Hunting asymptomatics: Are the opposition parties right about mass-testing?

As readers of my last post on manifesto pledges may have noticed, although the so-called opposition mostly don’t disagree with the government’s suicide- and bankruptcy-inducing Covid policies, they do disagree on one point: testing.

Indeed, one notable difference between Japan and other rich countries is how few tests Japan has conducted.

And in the early months of the pandemic, unless you were considered high risk, you had to have symptoms for 4 days before you’d be considered for a PCR test. And even then, you’d have had a hard time getting one. This lack of early testing is one reason (or excuse) for Japan wanting to set up its own CDC.

And the situation has changed less you’d think: during the Omicron wave, there were too few tests to meet demand.

So why hasn’t Japan ramped up testing capacity like other countries? One reason is the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare has seen little point in testing symptomless people who aren’t close contacts. Even the government’s top Covid “expert” Shigeru Omi said testing asymptomatics wouldn’t make much difference.

But this shortage of tests has meant that for over two years, Japan’s main opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), has been calling for a massive expansion of testing capacity. Hunting for asymptomatic cases was an integral part of their “Zero Corona” strategy outlined in early 2021.

Their plan was simple. Conducting periodic tests for essential workers, greatly expanding testing capacity, testing close contacts of close contacts, and isolating all positive cases and their close contacts would prevent resurgences of infections, thus allowing economic activity to continue without the need for states of emergency to be declared. Thankfully, the CDPJ has moved on from Zero Covid, but it still proposes expanding capacity so that free PCR tests can be given to whoever wants them.

And the Democratic Party For the People (DPFP) wants to have symptomless school children take periodic tests, in contrast to Japan’s panel of experts.

So since mass-testing of symptomless people is the main area of disagreement between the government and opposition, we might as well ask whether there’s any evidence for its effectiveness.

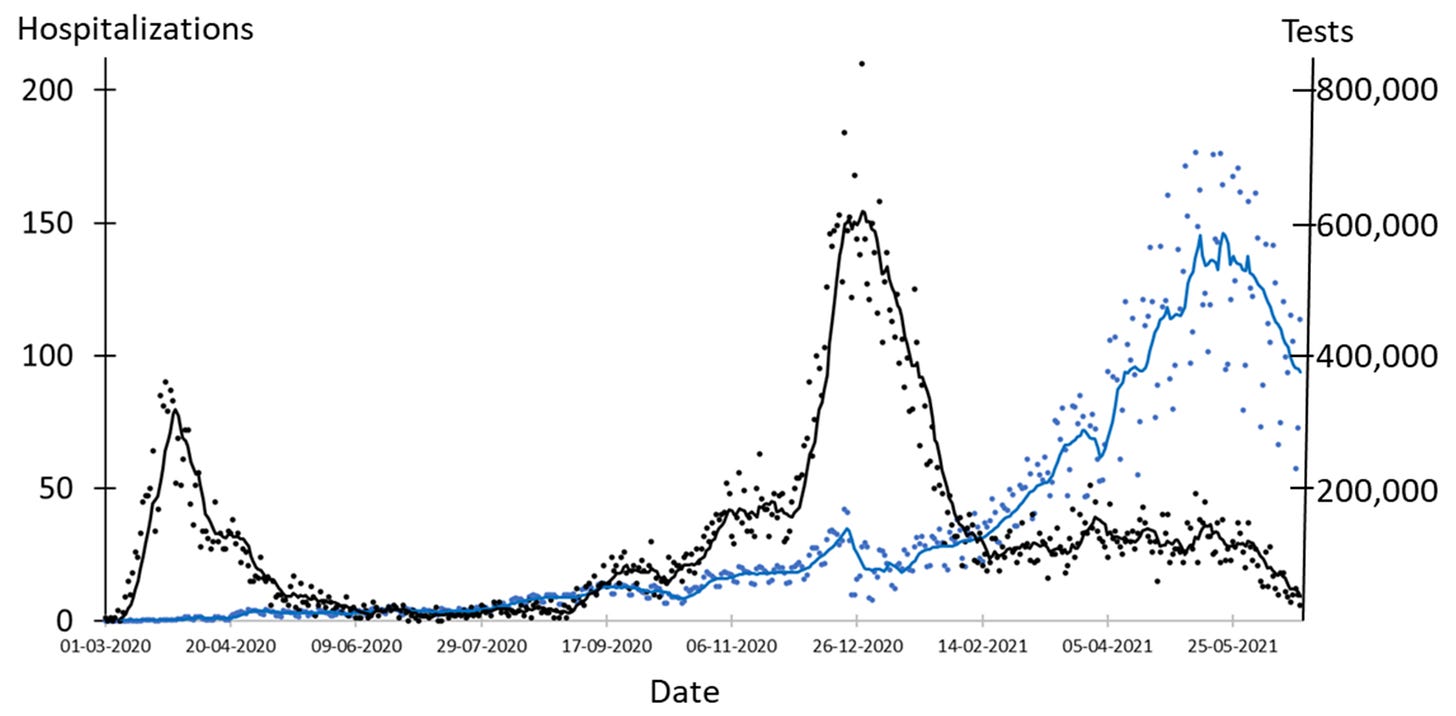

Busk et al. assessed the mass-testing strategy in Denmark up to June 2021 and found the number of tests did “not to correlate significantly with the number of hospitalizations during the pandemic.” They even found that “during the highest level of testing in spring 2021 the fraction of positive tests increased slightly; thus, the Danish mass testing strategy, at its best, failed to reduce the prevalence of COVID-19.”

However, these tests were taken at the individual’s initiative, and isolation after testing positive was voluntary. What about if almost everyone in a region is tested at the same time and positive cases have to isolate for 10 days?

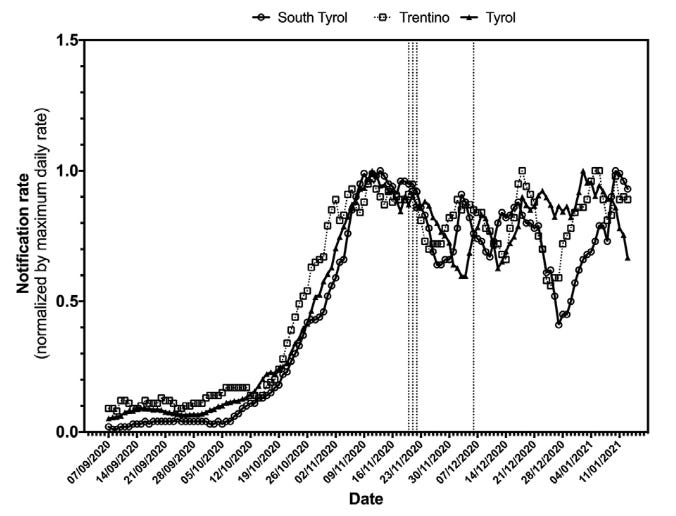

Ricco et al. analysed the effect of mass-testing of 67.9% of the population in the Italian province of South Tyrol over 3 days in November 2020 by comparing its case rate with those of neighboring Trento in Italy and Tyrol in Austria, where no mass-testing took place. Asymptomatic positives had to self-isolate for 10 days. To estimate the effect, “daily rates were percent normalized to their respective maximum values in order to cope with the different diagnostic strategies.” Put more simply, 1 on the vertical axis below represents the highest case rate during the period, and 0.5 represents 50% of it. Results showed that “epidemic curves of the three regions substantially overlapped until the end of December 2020, as sharing a common trend.” In other words, no effect could be found.

But mass-testing was only conducted once, and cases were already coming down before the intervention could take effect. Also, testing was voluntary, without any restrictions on people who declined to be tested. What about if the population is mass-tested twice earlier in the wave and refuseniks are quarantined?

In autumn 2020, Slovakia conducted nationwide mass-testing across 79 districts. Although testing was voluntary, anyone who declined to be tested had to quarantine for 10 days, so 84 and 87% of the eligible population agreed to be tested. Positive cases and their close contacts were required to isolate for 10 days. The districts where the positivity rate was above 0.7% were then subject to a second round of mass-testing one week later.

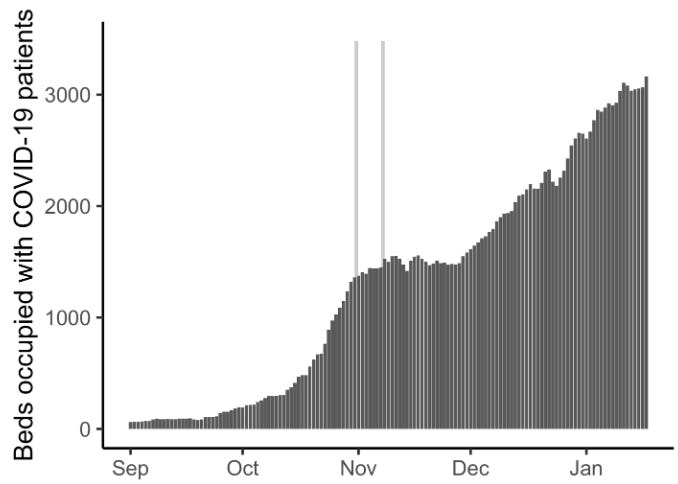

Using the districts that underwent one/two rounds of mass-testing as control/treatment groups, Kahanec et al. estimated that “the measured number of infections fell on average by up to about 30%” in the treatment districts following the second round. However, this effect “gradually faded out thereafter, with no significant impacts detectable three weeks after retesting.”

And a supplementary figure from a different paper on the same subject shows how Covid hospitalisations in Slovakia progressed after the rounds of mass-testing.

So the effect was fleeting. But what if mass-testing were conducted weekly?

Meredith et al. looked at the effectiveness of Cornell University’s Covid measures from August to December 2021. In addition to vaccination and mask requirements, over 60% of the campus community was tested each week, positive cases were required to isolate, and close contacts were traced and tested.

So how well did weekly mass-testing of symptomless people work?

Meredith et al. admit that “Cornell’s experience shows that traditional public health interventions were not a match for Omicron.” If mass-testing doesn’t work on an elite college campus, then it doesn’t work.

Then there are the problems caused by the inevitable false-positive (FP) results. Surkova et al. listed not just obvious financial ones like individual income losses, misspent funding, and business losses from funding workplace replacements but also societal ones like increased depression and domestic violence due to isolation and loss of earnings after FPs.

The problems of mass-testing aren’t any better for kids either. In the UK., The Pandemic Response and Recovery All-Party Parliamentary Group were told by Dr Angela E Raffle that “The net effect of the school testing is harmful because of the trauma of repeated testing and the disruption to children's lives through repeated exclusion and isolation.” Even more bluntly, Dr Zenobia Storah described the policy as “harmful, invasive and unevidenced” and “nothing short of state sponsored child abuse”. Someone should tell the DPFP.

So if there aren’t any positives to weigh against the negatives (pun intended), why do policy-makers like mass-testing so much? Analysing the correlates of Covid cases and deaths in 145 countries, Toya and Skidmore found “though use of PCR testing resulted in more recorded infections, it was unassociated with fatalities.” More tests = more cases.

Oh, that reminds me.

Here we go again!