Norwegian randomised trial finds masks associated with fewer sniffles but not fewer Covid cases or less healthcare usage

A new large-scale randomised trial of masks for preventing respiratory symptoms has been published by Norwegian researchers in the British Medical Journal called “Personal protective effect of wearing surgical face masks in public spaces on self-reported respiratory symptoms in adults: pragmatic randomised superiority trial”. So what did the authors do and find?

Between 10 February 2023 and 27 April 2023, 4647 participants were randomised of whom 4575 (2788 women (60.9%); mean age 51.0 (standard deviation 15.0) years) were included in the intention-to-treat analysis: 2313 (50.6%) in the intervention arm and 2262 (49.4%) in the control arm. 163 events (8.9%) of self-reported symptoms consistent with respiratory infection were reported in the intervention arm and 239 (12.2%) in the control arm. The marginal odds ratio was 0.71 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58 to 0.87; P=0.001) favouring the face mask intervention. The absolute risk difference was −3.2% (95% CI −5.2% to −1.3%; P<0.001)

Put simply, the mask-wearers had 29% fewer cases of self-reported sniffles over 14 days. So does this mean the mainstream media and mask-mandating authorities were right after all about anti-maskers being selfish, ignorant granny-killers? Not if we’re talking about Coivd.

No statistically significant effect was found on self-reported (marginal odds ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.98; P=0.82) or registered covid-19 infection.

You may recall that people worldwide were forced to wear masks because the authorities were adamant that masks worked against Covid specifically, not just the general sniffles. But in this study, rates of self-reported Covid are basically identical at a negligible 1.1% in both arms.

But at least by reducing general sniffles, masks surely lower your chances of needing medical care, right? And lowering the burden on the health service was the main initial justification for the Covid restrictions (“Stay Home, Save the NHS” and all that). But no effect was found for healthcare utilisation either.

In total, 144 (6.3%) participants in the control arm and 102 (4.5%) in the intervention arm reported needing healthcare during the trial. Of these participants, 29 (20%) in the control and 23 (23%) in the intervention arm reported that this was due to respiratory symptoms, whereas 40 (28%) participants in the control arm and 27 (26%) in the intervention arm reported other reasons.

This result brings up a question that apparently didn’t occur to the study authors: If masks really reduced respiratory symptoms by 29%, why were the numbers of subjects needing healthcare for respiratory symptoms almost identical across both arms? One reason could be reporting bias. In fact, that’s what the subgroup analysis suggests.

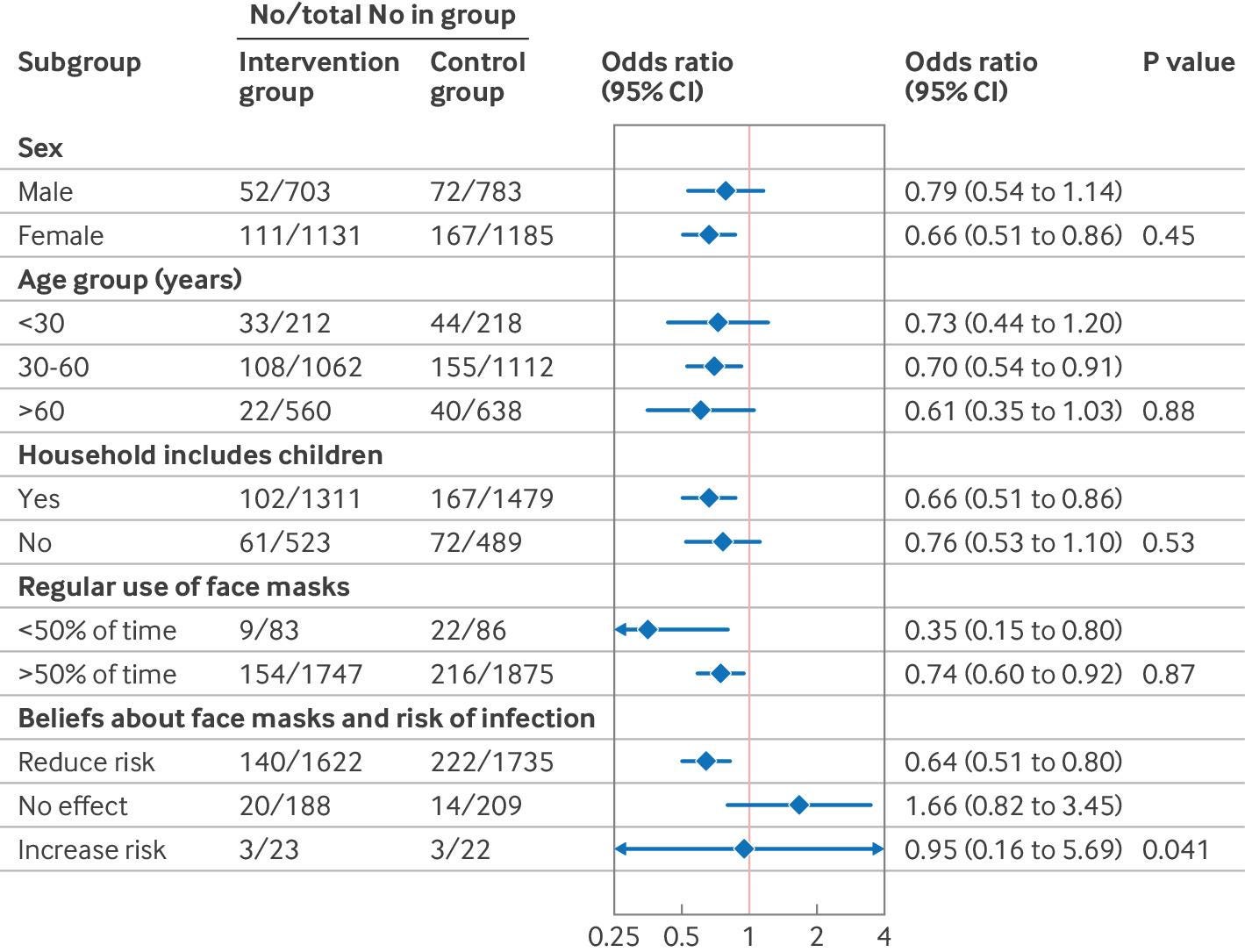

Figure 2 shows results for the prespecified subgroup analyses. The only analysis for which significant effect modification was estimated was for participants’ beliefs about wearing face masks and risk of infection (P=0.04 for interaction). A beneficial effect was estimated for participants who reported that they believed face masks reduced the risk of infection. Estimates for participants who reported that they believed face masks had no effect or increased risk were consistent with benefit, no effect, and harm. However, owing to the small number of events in these subgroups, the confidence intervals were wide and therefore these estimates lack precision.

In other words, mask-wearers (non-wearers) who believed masks to be effective reported fewer (more) sniffles. Meanwhile, the effect was reversed for non-believers, although they were a smaller number. This means that either the effect of masks depends on the belief of the wearer, or there was some bias in the reporting. My money is on the latter.

The authors themselves acknowledge the problem of bias as one of the study limitations. They also point out that masks may also affect the behaviour of the wearers and those around them.

The group allocation might also have led to additional effects on participants’ behaviour. For instance, a higher proportion of participants in the control arm reported attending cultural events [39% vs. 32%] and restaurants [62% vs. 53%] during the trial period. Furthermore, some participants in the intervention arm reported feeling awkward wearing face masks when there was no official requirement to do so. This finding may imply that non-participants tended to keep a larger social distance from participants in the intervention arm, which could be seen as an inherent effect of wearing face masks.

Numerate readers might note that the absolute differences between the two arms were larger for going to cultural events (7%) and restaurants (9%) than for self-reported respiratory symptoms (3%). This suggests that having to wear a mask in public is more likely to keep you home than keep you healthy.

In summary, this study suggests that masks (1) can reduce general sniffles a bit (but only if you believe they do) without reducing Covid cases or need for healthcare and (2) can make wearers less sociable. A cynic might conclude Effect (2) was the point of the mask mandates all along.

It's been a while. I was begininng to think you had been abducted by the Covidians. Perhaps you just had the sniffles.

Always great to read your analyses, my friend, gaijin Guy Gin! I'll be up in Tokyo in November, and in your honor, I'm bringing some incredible local Gin for you.