What will convince the Japanese to unmask?

Although the national government recently said people could take off their masks while outside, 2 meters from other people, and not talking…

…most Japanese are continuing to mask up outside no matter what.

According to a Japanese-language report, 30 students and 1 parent/guardian were taken to hospital with suspected heat stroke. One person had breathing difficulties, 25 couldn’t walk, and 1 student was hospitalised.

In answer to the question you’re all thinking, about 40% of all students were wearing masks even though the school staff had said they could take their masks off. The max temperature in Osaka that day was 29 degrees.

So what will it take for the Japanese to breathe freely again and avoid similar mask-casualty events [1]? Well, 708 people aged 20-59 were asked that, and their responses were as depressing as you’d expect. Note multiple responses were possible.

So only 30.3% would be convinced by the government saying it’s okay. Remember that Japan doesn’t have legally enforceable mask requirements, although masks are mandated in all but name in elementary, junior-high, and high schools. Depressingly, only 12% said masks could be taken off now, which shows how deeply held the superstitious belief in masks has become here. As for effective medications, there are many but none that is both effective and profitable.

But there’s a certain rational self-interest to masking in Japan. For example, take a look at the results when the same 708 people were asked for their impression of people who don’t wear masks.

Knowing how unmasked people are thought of by over 60% of the population, even people who know masks aren’t much use will wear them to not stand out or give a bad impression, not to prevent infections.

And this is consistent with a 1000-person survey conducted in March 2020, in which “a powerful correlation was found between perception of norms and mask usage; conformity to the mask norm was the most influential determinant... Feeling relief from anxiety by wearing masks also promoted mask use.” Put simply, the respondents mainly wore masks because it was a social norm, with relief from anxiety a weak second place. That norm is even stronger now than in March 2020, when 40% of respondents said they wore masks not at all or only sometimes. Universal masking didn’t fully take off until April 2020. Up to late March, even the people in charge of Japan’s Covid response were mostly bare faced.

But universal masking has been the norm for over two years. And because people who don’t follow social norms are viewed negatively, “No one wants to be the first person to remove their mask”, as a Japanese interviewee in the Guardian recently put it. As the Japanese saying goes, the nail that stands up gets hit back down.

Interestingly, in contrast to respondents in 2022, the respondents in March 2020 had realistic expectations of mask effectiveness and necessity: “frequency of mask usage depended much less on the participants’ perceived severity of the disease and the efficacy of masks in reducing infection risk both for themselves and for others.”

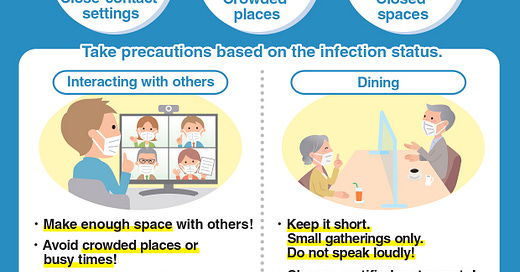

This difference could be due to sampling bias, but then again, the 2022 respondents have had 2 years of nonstop pro-mask propaganda coming at them from all angles, including the government telling them to wear masks during Zoom calls and between bites and sips while dining.

And as I’ve mentioned before, there is another big reason for masking in Japan: not wearing a mask increases your risk of having to self-isolate at home for 10 days as a close contact. This was explicitly stated by the staff at pre-schools in Nayoga in another recent report.

The school staff said it’d be better if the kids didn’t wear masks but they asked them to do so anyway. This is because if the kids don’t wear masks and someone tests positive, more kids will be classified as close contacts and the school will have to temporarily close, which means parents having to take time off work to look after their kids. Their position was that masks are a close contact classification, not infection, prevention measure.

So even if the government says it’s okay to unmask, it won’t matter much if they don’t change (or even better, scrap) the close contact classification criteria.

But even then, there will be plenty of people who won’t give up their masks come hell or high temperature. The responses below come from 1000 people asked in February about their intentions to keep masking after the Covid-19 Pandemic ends (whatever that means).

Yes, 54.5% want to wear masks indefinitely. Common reasons given for wanting to keep masking were not having to shave/do make up.

But some Japanese had mask addictions before Covid, so it looks like the problem has only become much, much worse.

And even in 2012, academics were able to publish papers with titles referring to masks as safety blankets for the Japanese.

The paper states that “A historical analysis suggests that an originally collective, targeted and science-based response to public health threats has dispersed into a generalised practice lacking a clear end or purpose.”

The only part of that sentence which isn’t even more true today is “science based”.

[1] A similar incident happened the very next day involving 22 junior-high school students who had been practicing for a sports day outside in 25-degree heat while masked. The difference was the so-called educators at the school had instructed the kids to keep their masks on.