Why has Japan had so few Covid deaths (Part 5)? Was it international travel restrictions? (Updated 29 July)

tl:dr No

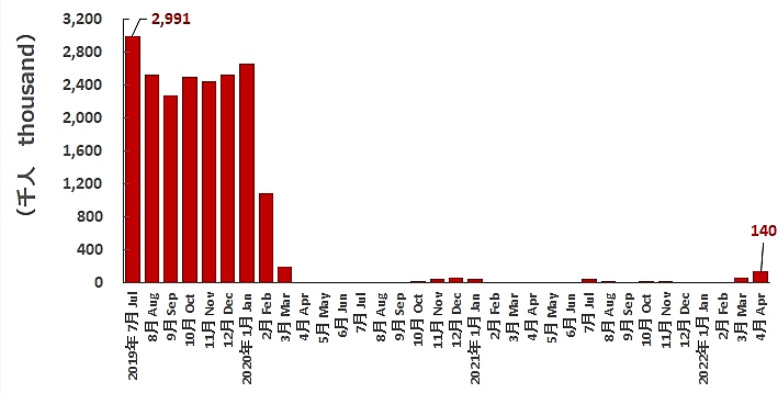

In honour of Japan restarting inbound tourism by letting foreign biohazards in to be taken around random parts of the countryside in North Korean style monitor tours, I decided to add Part 5 to this series (previous parts covered the 3 Ms (mindo, mobility, masks) and immunological factors).

Like the 3 M’s, international travel restrictions (ITRs) are unlikely to explain much of the Japan-West Covid mortality gap for 3 reasons.

The mortality gap predates the travel ban

Not only did Sakoku 2.0 start about one week after actual infections had peaked in Japan…

…it started as the 7-day average of reported deaths peaked in Spain and Italy. Even at this early stage of the pandemic, the Japan-West mortality gap was well established.

Also, almost all of Europe and the Americas introduced either bans on people from certain regions or total border closures at least 2 weeks before Japan’s entry ban. So claiming Japan’s low Covid deaths are due to ITRs doesn’t even reach the level of the Post Hoc Fallacy, unless you want to claim that ITRs increase Covid deaths.

But how widespread was the virus before the entry ban? In a seroprevalence survey in Kobe conducted 31 March to 7 April 2020, Doi et al. estimated that 3.3% of the city’s population had been infected, meaning “396 to 858-fold more than confirmed cases with PCR testing in Kobe City.”

And in a seroprevalence survey in Tokyo conducted 21 April to 20 May 2020, Takita et al. estimated that 3.83% of the city’s population had been infected, which would equate to about 530,000 people. The cat wasn’t just out of the bag- it had given birth to lots of kittens.

These surveys were included in the meta-analysis by Ioannidis published by the WHO. He estimated the infection fatality rate in Japan to be 0.02-0.04%, compared with a global median of 0.23% and a median of 0.57% in locations that had more than 500 COVID-19 deaths per million up to September 2020 (e.g., Brazil, Spain, and parts of America).

Put simply, the entry ban was pointless because SARS-Cov_2 was already well settled in Japan before Sakoku 2.0 started, but it has a harder time killing the Japanese (and northeast Asians generally) due to numerous immunological factors.

Higher deaths during Sakoku 2.0 than before

Japan’s Covid deaths were higher in later waves while the borders were mostly closed than in the first wave when infections peaked before the entry ban.

So if anyone wants to say “It would have been worse if Japan had let tourists in,” they first need to explain why it wasn’t worse when Japan was still letting tourists in at the start of 2020.

International travel restrictions aren’t effective

In its 2019 pandemic response guidelines, the WHO did not recommend border closures in any circumstances. In fact, the guidelines reject or ignore most of the authoritarian policies politicians and public health officials have come to love.

The document mentions that “travel restrictions may only delay the introduction of

infections for a short period,” which seems to perfectly sum up Japan’s experience with Omicron.

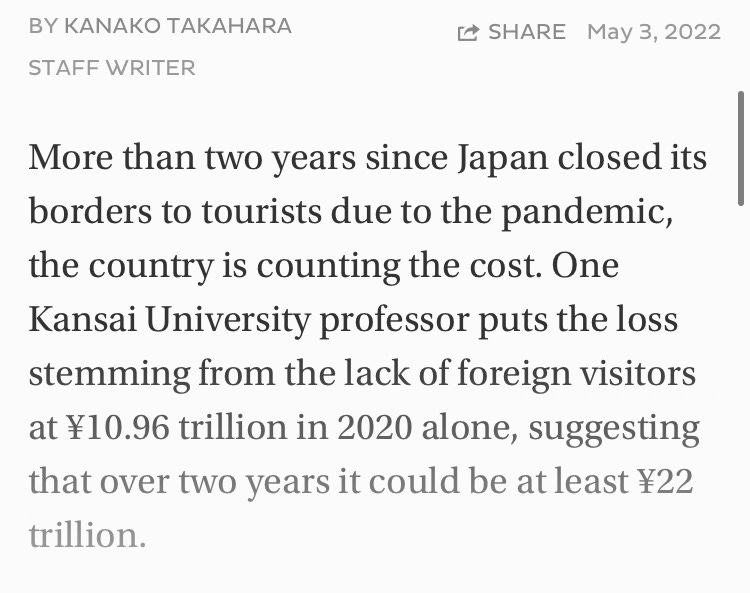

It also states that “Border closures may be considered only by small island nations in severe pandemics and epidemics, but must be weighed against potentially serious economic consequences.” Japan may be an island nation, but it isn’t small (pop 125 million) and Covid’s 0.02-0.04 IFR can hardly be called severe. The economic consequences have certainly been serious though.

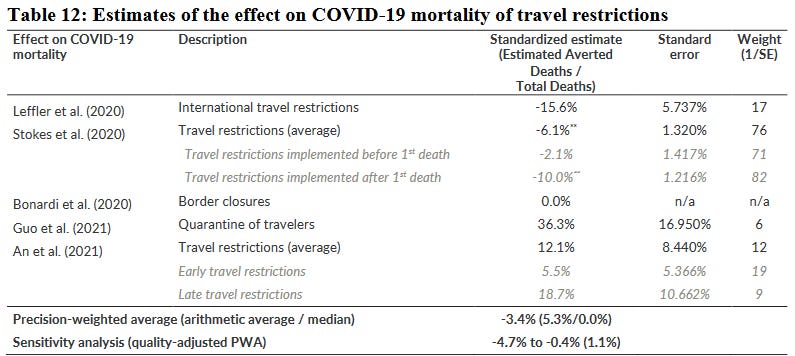

But the WHO’s guidelines are pre-Covid. So how well have ITRs worked in the Covid era? In their meta-analysis of mandated non-pharmaceutical interventions, Herby et al. estimated that “Travel restrictions reduced Covid mortality rates by 3.4%” with a span from 0.4 to 4.7% in the first half of 2020. Opinions may differ, but I don’t think that would pass too many cost-benefit analyses.

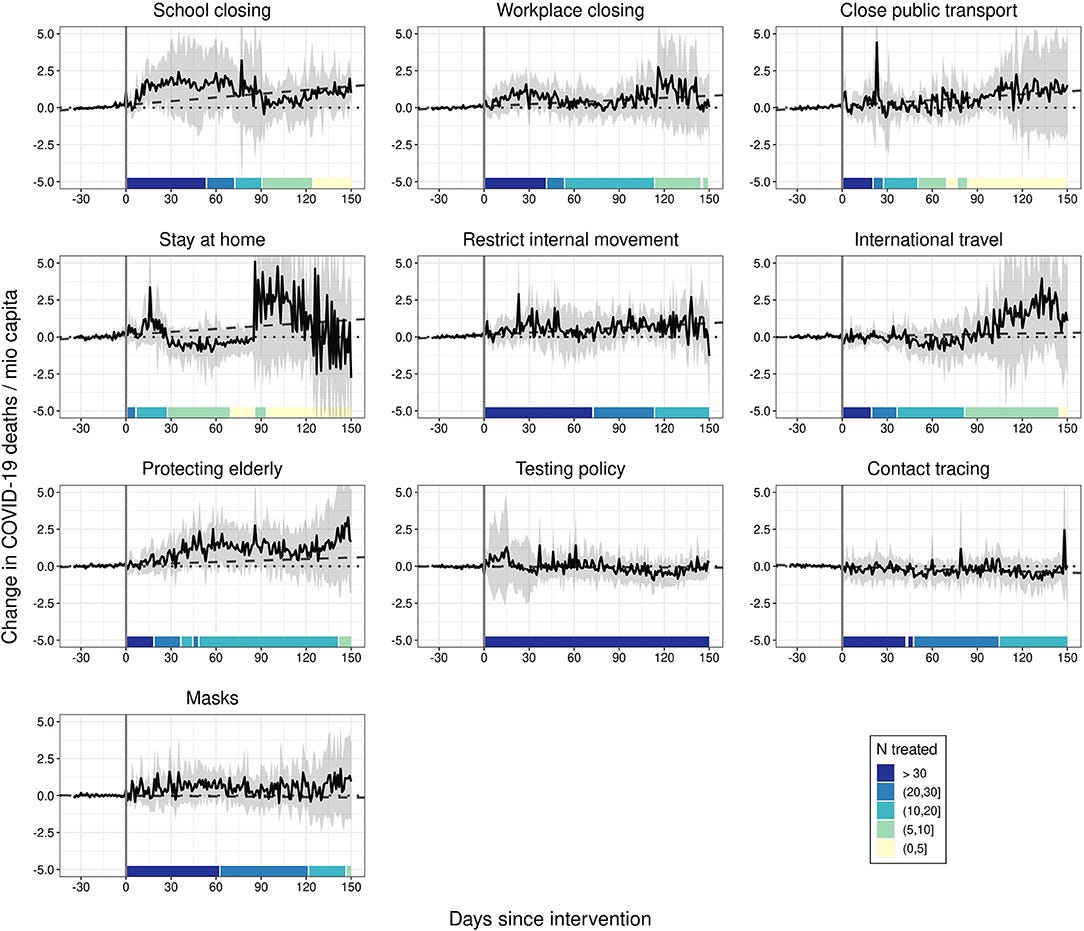

But what about ITRs after the first half of 2020? In a study covering 169 countries from 1 July 2020 to 1 September 2021, Mader and Rüttenauer did “not find substantial and consistent COVID-19-related fatality-reducing effects of any NPI under investigation,” including ITRs. In the below figure, an intervention is regarded as effective if the solid black line and its gray confidence intervals (CIs) are below the dashed black line. The solid black line and its CIs for international travel are clearly not below the dashed black line.

These studies are pre-Omicron. But because Japan was one of the few countries to ban entry of non-resident foreigners during the Omicron wave, we can see how well border closures work by comparing Japan with the world average.

But at least the ban was popular.

So all that’s left to do now is book your tickets, pack your bags, and put on your mask because for the first time in two years, Japan welcomes you with arms wide open!

You might want to read this first though.

Update 29 July

I’ve written about this in another post, but I’ll repeat it here because it’s relevant. Japan’s neighbour South Korea opened up and had 227,000 tourists in June compared with 252 in Japan. This means we now have closest thing possible to an ITR RCT. The results are as I would’ve predicted.