How did Japan achieve a high vaccination rate without coercion?

tl:dr Propaganda and peer-pressure

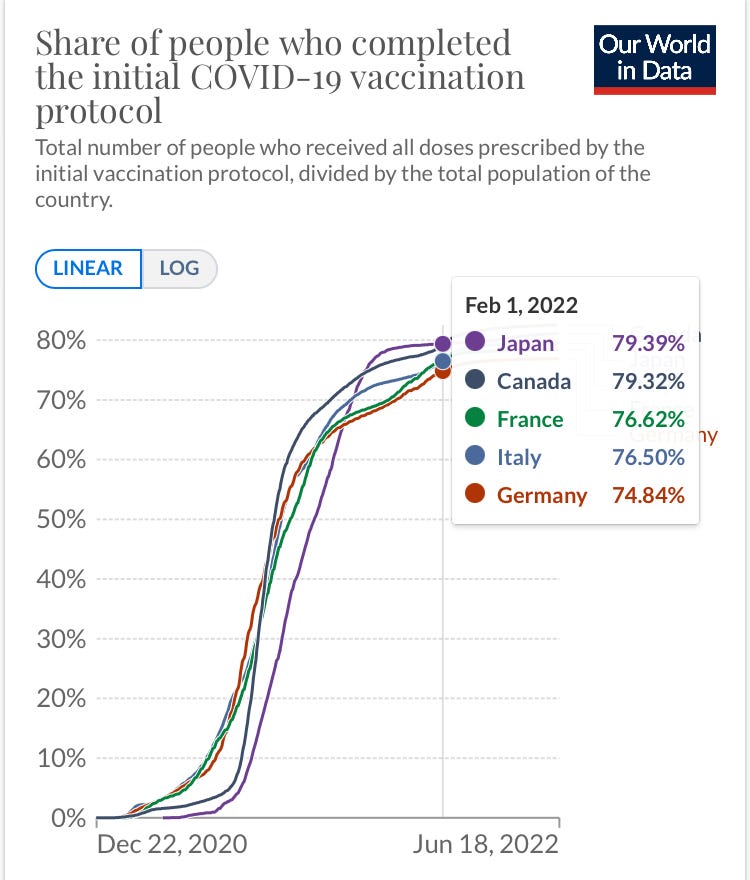

A new study looked at the effect of introducing mandatory proof of vaccination requirements (what I prefer to call vaccine coercion) on vaccination rates in France, Italy, Germany, and Canadian provinces. The results suggest vaccine coercion increased the rate of first doses among people aged 12 and over by about 8% in France and 12% in Italy but less in Germany and Canada.

Finding that vaccine coercion raises vaccination rates is hardly revolutionary though, is it? It’s like finding mugging is more profitable than begging.

Japan, in contrast, hasn’t engaged in vaccine coercion. This has led several western commentators to applaud Japan for its liberal stance in favour of medical freedom.

And apart from Saitama requiring a vax pass/negative test to buy booze and the governor of Yamanashi telling the unvaxed to not leave the house earlier this year, it’s true that Japan hasn’t discriminated against or persecuted the unvaxed like the countries above. But that’s because of legal/constitutional restraints, not because Japan’s decision-makers are nice people. The same goes for Japan not locking down: it legally/constitutionally can’t (yet).

Also, the Japanese had less incentive to get vaccinated considering how much lower Japan’s Covid mortality was compared with the west before the jabs became available

So how did Japan get higher vax rates than France, Italy, Germany, and Canada without coercion? I want to focus mainly on the initial two-dose schedule.

Of course, Japan’s government and media have been gung ho in their support for the jabs, but they don’t demonise the unvaxed like governments and media elsewhere. Elderly Japanese were easily persuaded to get the jabs by TV telling them how dangerous Covid was to them, but what factors were exploited to persuade so many low-risk younger Japanese to get the jabs?

Cultural factors probably play a role. In a seminal paper written in 1991, Markus and Kitayama claimed that “Many Asian cultures have distinct conceptions of individuality that insist on the fundamental relatedness of individuals to each other. The emphasis is on attending to others, fitting in, and harmonious interdependence with them.”

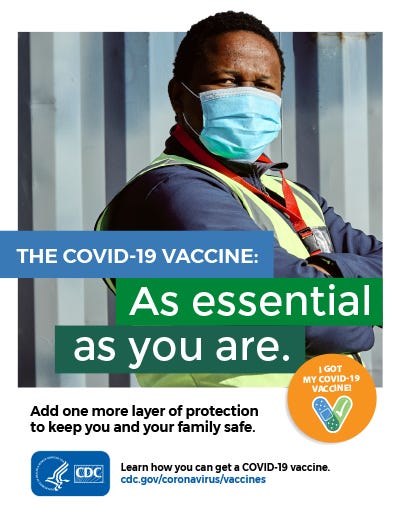

And vaccine promotion/propaganda in Japan has been based on appeals to interdependence. Let’s take a look at a representative CDC poster aimed at Americans.

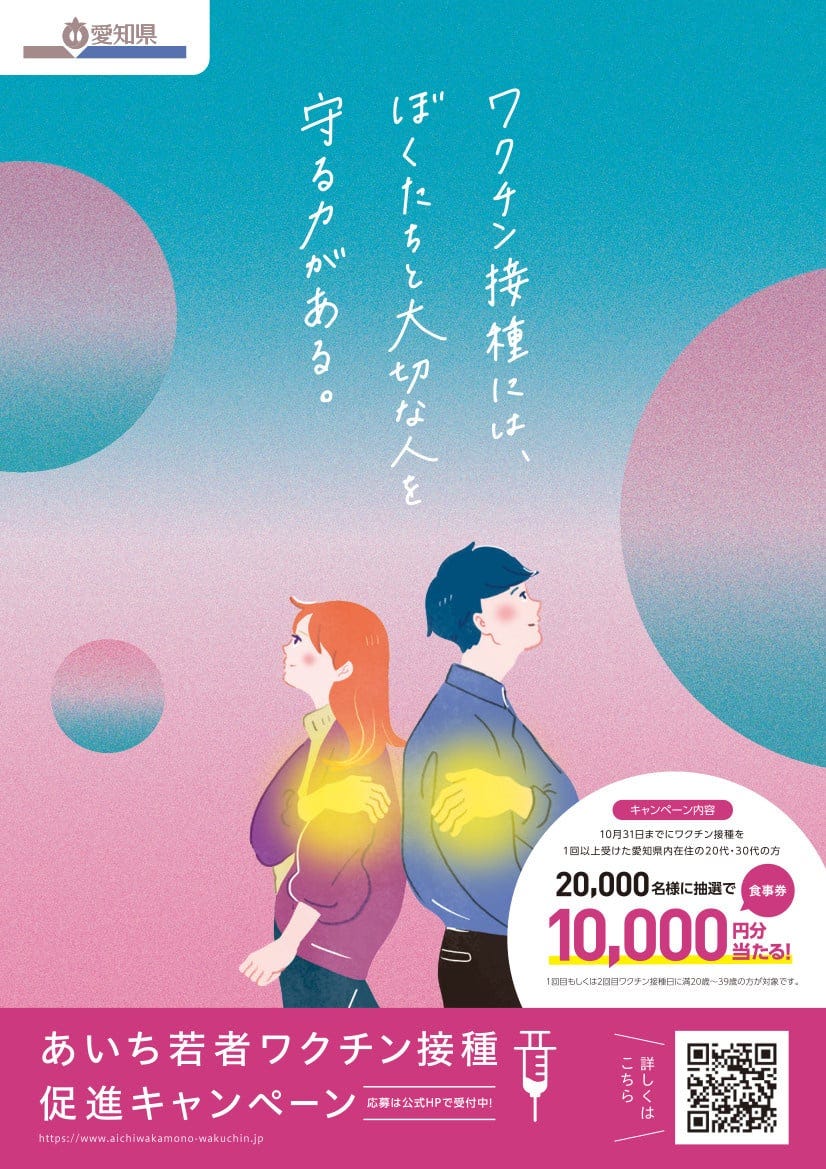

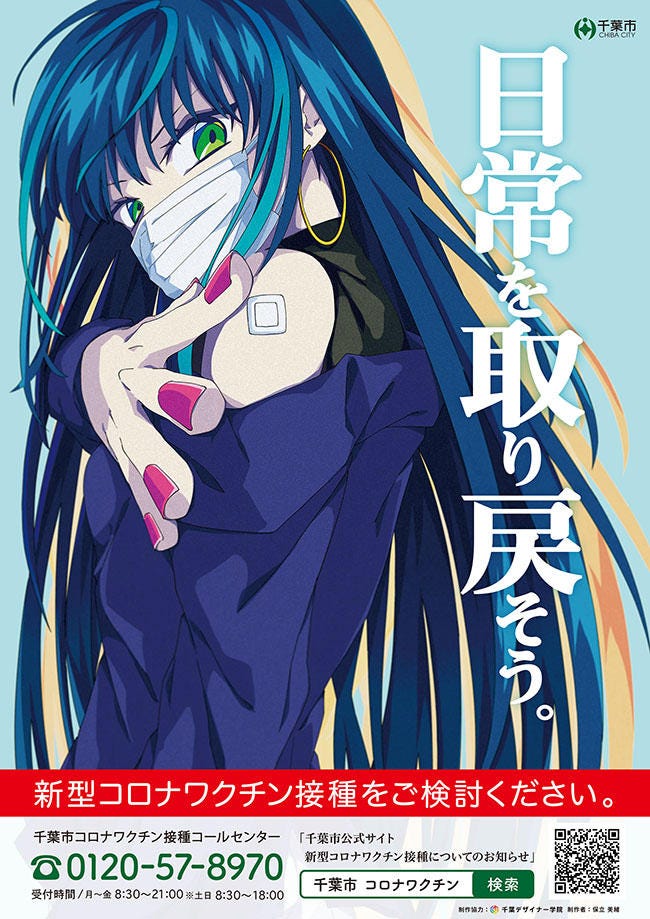

The poster appeals directly to the individual. Compare the CDC’s tag line (“As essential as you are”) to the standard line in Japanese posters: “To protect your loved ones” (大切な人を守るため).

One good, and skin-crawling, example of propaganda exploiting the interdependent view of self is Fukuoka’s Consideration Vaccine poster telling people to get vaccinated out of consideration for others.

Also, because younger people need more persuasion to get a vaccine for an old-person’s disease, Japanese vaccine propaganda appeals to the young to get jabbed to protect their elderly relatives. Notice how sentimental these posters are.

So is there any data to prove that many Japanese got vaccinated for their families rather than themselves? Yes, there is. In a survey conducted in March 2021 (when “95% effectiveness” could still be said with a straight face), 48.6% of respondents who said they wanted to get vaccinated gave the reason as protecting themselves (自分の予防) and 45.5% gave it as protecting those around them (周りの人の予防). 5.3% said they needed it for work, e.g. healthcare workers who faced intense peer-pressure or business people who needed to travel internationally.

But even more important in understanding Japan’s high vax rate (and universal mask compliance) is Markus and Kitayama’s second sentence: “The emphasis is on attending to others, fitting in, and harmonious interdependence with them.”

The prioritisation of harmonious relations makes Japan a pleasant and safe place to live most of the time, but maintaining this harmoniousness requires the individual to not only go along with the majority but also follow instructions from those higher in the hierarchy. However, the problem with prioritising harmoniousness is that nobody wants to rock the boat even when it’s heading in the wrong direction. This is a major reason for continued universal masking and other Covid nonsense in Japan: nobody wants to stand out and be thought of as a trouble-maker.

And like wearing masks, there’s no law requiring or coercing you to take the Covid jabs. But if everyone else at your school or workplace is taking them, then you risk being thought of negatively if you don’t. And if your employer sets up a shooting gallery on the premises, then they are making it quite clear what they want you to do.

How well do you think you’d handle that level of pressure? Japanese TV even reported the complaints of people who felt intense peer-pressure to get jabbed.

This workplace peer-pressure is aided by the fact that if you test positive for Covid, you will cause bother (迷惑 meiwaku) for many of your colleagues because they will be asked to self-isolate. And you can’t understand Japanese people’s response to Covid without understanding how central the desire to avoid causing meiwaku is. Even people who know Covid isn’t particularly dangerous to them and know masks don’t work will still stay home when the government requests it and wear masks when they go out in order to avoid the social sanctions and bother caused by testing positive.

A 2020 article titled “Many people fear self-isolation and (social) sanctions more than Covid itself” quotes one working-age Japanese saying the following: “Even if I get Covid, I’ll probably get over it the same as a cold. But I’m scared that I’d cause meiwaku for and become resented by my coworkers and clients for making them close contacts.” Another said, “If I get Covid, it’ll probably be mild for me. But I definitely want to avoid it because my kids would have to take time off school and may be discriminated against and cast out by their friends.” You need to remember this whenever you read western mainstream media reports saying things like “The Japanese remain cautious of the virus.” The reality is many Japanese are much more cautious of Japanese society’s disapproval than the virus, and understandably so.

Also, because of the shame and stigma attached to Covid in Japan, when outbreaks of PCR positives occur within schools or organisations, representatives hold press conferences to apologise.

Put simply, testing positive will not make you popular. So in 2021, there was a strong social incentive to get jabbed because if your coworkers did and you didn’t and then you tested positive, causing your vaxed coworkers to self-isolate, you risked being widely resented. Again like masks, vaccines were for protecting reputations too. And again like masks, the government cynically incentivised vaccines through its policy of close contact isolation.

Additionally, another carrot waved in front of the faces of the youth was the prospect that getting two jabs would lead to the lifting of Covid restrictions.

Which was of course a lie.

But since it’s become clear to all but the most obtuse Covidians that the vaccines don’t protect anyone from infection, booster uptake hasn’t been as high, especially in younger age groups. It’s still about 60% overall though.

But by not being able to resort to vaccine coercion, Japan has avoided generating large amounts of anger like France did.

Like the results in the vax-passport study above, finding people are more angry after being coerced into vaccination is like finding people are less happy after giving their money to muggers than to beggars.

Japan’s lack of vaccine coercion has also meant it has avoided numerous ethical problems.

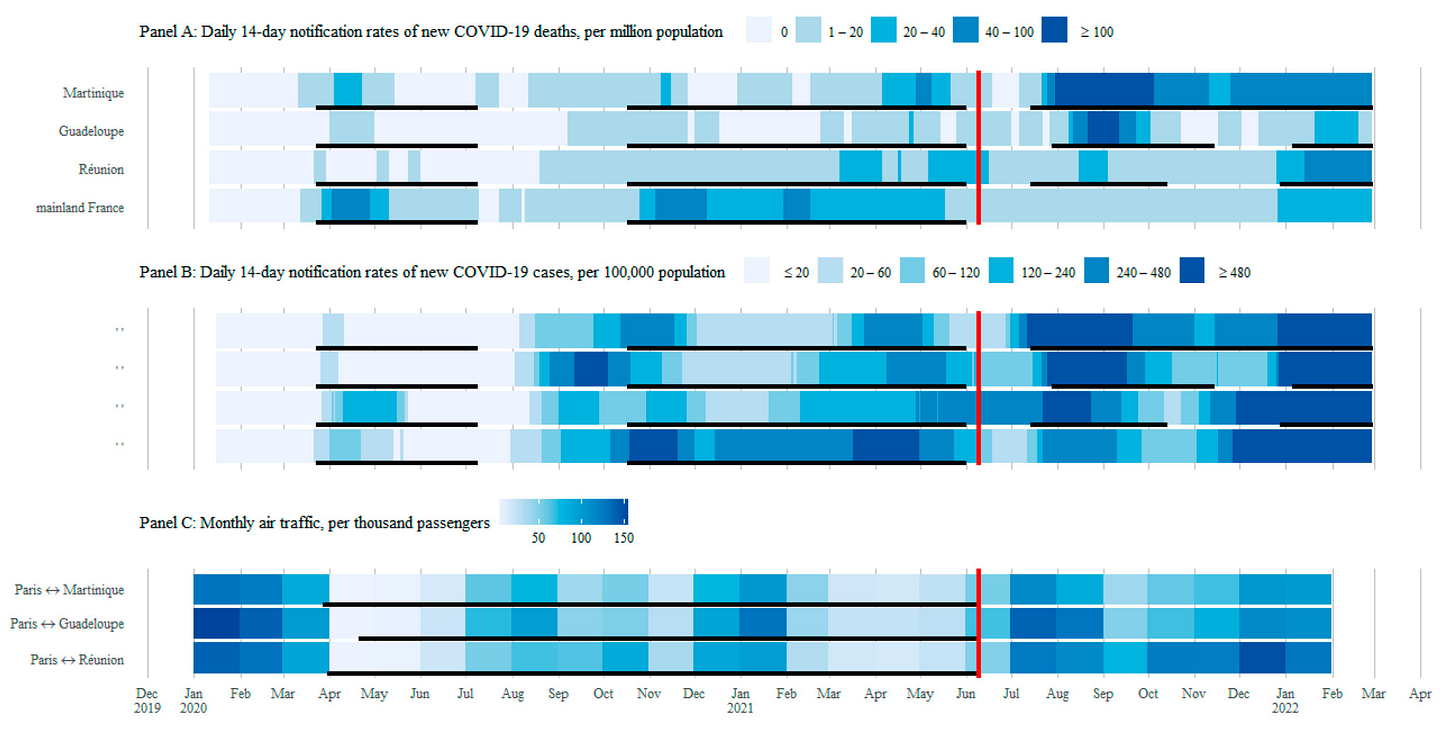

And to ensure there are no “Yes, buts” here, the one study on the real-world effectiveness of vaccine passports (for quarantine-free travel from mainland France to the French Caribbean) found the cases and deaths increased after the system was implemented.

Ultimately, the lesson to learn here isn’t particularly inspiring: propaganda and peer-pressure can work as effectively as and possibly even better than coercion. This is similar to the lesson learned from non-pharmaceutical interventions in Japan and overseas too: media-driven hysteria and government requests can work just as well at making people stay home as legally enforceable shelter-in-place orders.

So governments don’t need to use coercion to get most people to do what they want them to do. But they will continue to use coercion on the disobedient few- they enjoy it too much.