Suicide in Japan during Covid: no country for young women (Updated 19 June 2022)

A review of the literature

After writing two posts touching on this issue (here and here), I thought I’d review the peer-reviewed scientific literature on the depressing subject of suicides in Japan during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

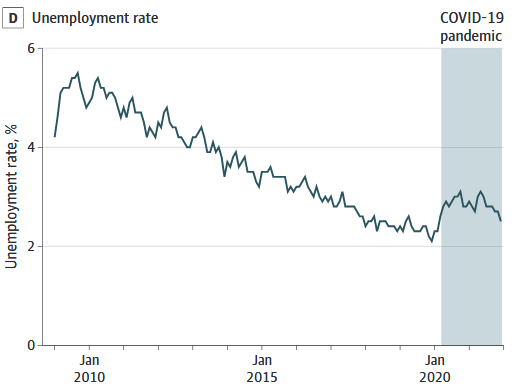

First, note that although Japan’s rate was considerably higher in the past, the pandemic (more accurately, the reaction to it) reversed a decade-long secular decrease and resulted in excess suicides in both 2020 and 2021, as shown by Horita and Moriguchi. The large rise in 2011 was a result of The Great East Japan Earthquake.

They also noted the correlation between the suicide rate and unemployment rate.

Because Japan was still mostly living the Old Normal in Jan-March 2020, Horita and Moriguchi looked at fiscal years (April-March) rather than calendar years. The below graph clearly shows notable rises in men in their 20s and women under 80 but especially in their 20s.

Up to September 2021, they estimate that “the incidence of suicide was higher than the estimation by 17.0% (95% CI, 11.4%-22.7%; P < .001) for men and 31.0% (95% CI, 22.8%-39.2%; P < .001) for women.”

In terms of absolute numbers, Kurita et al. estimated there were 2276 excess suicides up to January 2021.

But completed suicides alone don’t tell the full story. Habu et al. looked at the data for completed and failed suicides in Okayama City and Kibichou (combined pop: 720,000) between March and August in 2018 to 2020. The rise was most pronounced in women aged 25-49, increasing from 43 in both 2018 and 2019 to 73 in 2020.

So what are the specific reasons for this? Koda et al. investigated 21,027 suicides (70.2% of the total) for which the reason was indicated between Jan 2020 and May 2021. The reasons were separated into 7 categories: family, health, economy, work, relationship, school, others (e.g., copycat suicide). There were months with excess suicides (pink bars) in all categories for women and all but school for men. Women also had more months of excess suicides related to family, health, work, relationships, and others than men.

Among the 57 subcategories, there were 22 with at least one month of excess suicide for men, with economy and work subcategories accounting for 9. Koda et al. suggest that “The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have been severe enough for many men to resort to suicide.”

There were 24 subcategories with at least one month of excess suicide for women, with family subcategories accounting for 6. Koda et al. suggest that “school closures, telecommuting, an increase in caregiver role, and restrictions in access to health services were associated with women spending more time with family members; this may have been associated with the excess suicide rates we observed by exacerbating parent-child problems, other family discords, child-rearing problems, and caregiving fatigue.”

Interestingly, women had months of excess suicides related to mental health issues (depression, schizophrenia, other mental disorders) but men didn’t.

In terms of suicidal ideation, Yamamoto et al. surveyed people living in urban areas in May 2020 (Wave 1) and February 2021 (Wave 2) to investigate the effects of Japan’s repeated state of emergency (SoE) declarations on mental health. They found lower rates in Wave 2 than in Wave 1 but “the degree of reduction in suicidal ideation was significantly smaller among women than men.”

It’s worth noting that whereas most schools and “non-essential” businesses were closed in the first SoE, the second SoE mainly involved bars and restaurants closing at 20:00. Yamamoto et al. suggest that the reduction in suicidal ideation and other psychological symptoms may be because “difficulties in home, work, and school life were reduced in the second wave compared to the first. Further, in the second wave, both consumption activity and mobility tended to increase.”

However, they also found that “Only the 18–29 years age group displayed no reduction in suicidal ideation from the first to the second wave” and “those with a history of treatment for mental illness and those with an income of < ¥2 million [<US$15,500] had a particularly high rate of suicidal ideation.”

All the above results are supported by a survey conducted by Yoshioka et al. into serious psychological distress (SPD) in August and September 2020. Overall, 10% of the 25,482 respondents met the criteria for SPD with significant risk factors including being a women, aged 15-29, low-income, providing caregiving to family members, experiencing domestic violence, and fear of Covid-19.

Additionally, Covid-19 related stigma was also associated with SPD among women aged 15-29, 15% of whom met SPD criteria. See my last post for an example of the damage caused to young people by the fear of this stigma.

Discussing possible reasons for these results, Yoshioka et al. mention the economic downturn and social isolation due to social distancing and the first SoE but also suggest that “as COVID-19 spread and society dramatically changed, fears about COVID-19 gradually developed making people psychologically unstable.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Update 19 June 2022

In a new paper, Yoshioka et al. estimate there were over 3000 excess suicides in Japan from April 2020 to December 2021.

Breaking the male results down by age group, “statistically significant results were observed among men aged 20–29 and 40–49 years, with 466 (95%CI: 169 to 763) excess deaths in the former and 423 (95%CI: 97 to 749) in the latter.”

The results for women are even worse, with statistically significant results in all age groups apart from those under 20, 40–49, and 80 years or over: “the highest number of excess deaths was observed in women 30–39 years (421, 95%CI: 242 to 600), followed by 396 (95%CI: 189 to 603) in women 60–69 years, 352 (95%CI: 117 to 587) in women 20–29 years, 325 (95%CI: 98 to 551) in women 70–79 years, and 322 (95%CI: 63 to 582) in women 50-59 years.”

Yet more evidence that these deaths are due to the response rather than the pandemic itself is provided by Okada et al., who looked at age-standardised death rates by suicide (SDR). They found significant increases for women in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions.

Moreover, they conclude that “transformed lifestyles during the pandemic, increasing time spent at home, enhanced the suicide risk of Japanese people by hanging and at home.”

But these aren’t their most interesting findings. The found that metropolitan and non-metropolitan female SDRs correlated with Covid cases but not Covid mortality. The authors don’t discuss the reason for this, but these results suggest at-risk Japanese females are more susceptible to the media’s hysterical Covid reporting.

In contrast, non-metropolitan and metropolitan male SDRs didn’t correlate with Covid cases, but there was a correlation between Covid mortality and non-metropolitan male SDRs.

Overall, these new results offer even more depressing proof that the cure has been much worse than the disease in Japan.