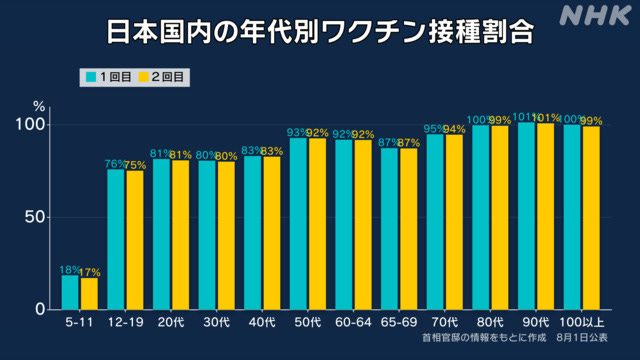

After previously venting about western mainstream media imploring its readers to give up their individualistic ways and unquestioningly stick masks on their faces like East Asians apparently do, I’ll look at the evidence provided by Covid vaccination intention surveys of the Japanese that East Asians are in fact able to think as individuals. These surveys were conducted to identify demographics that are skeptical of the newly concocted gene juice and think up ways of persuading (or coercing) them into taking it, but I want to see if they also offer hints for how vax skeptics can convert people to their side. To do this, I’ll look at results of surveys taken before and after the jab campaign really got going in Japan in mid-2021.

Pre-campaign surveys

Okubo et al. analyzed the results of 23,142 survey respondents aged 15-79 in Feb 2021 and found 11.3% were “vaccine hesitant”. Unsurprisingly, “the proportion among younger respondents was more than double that among older respondents.”

Factors associated with the hesitancy were female sex, living alone, low socioeconomic status, and presence of severe psychological distress, especially among older respondents.

So the average vaccine hesitant Japanese is a lonely young single woman with low SES and mental health issues. No doubt she’ll become a cat lady if she lives long enough.

The top reason for hesitancy was worry about adverse reactions at 73.9% (not unreasonable), with doubts about effectiveness in second place at 19.4% (again, not unreasonable). Maybe those future cat ladies were on to something. Only 7.5% chose “I think I have a low risk of getting seriously ill” even though that applies to over 99% of Japanese.

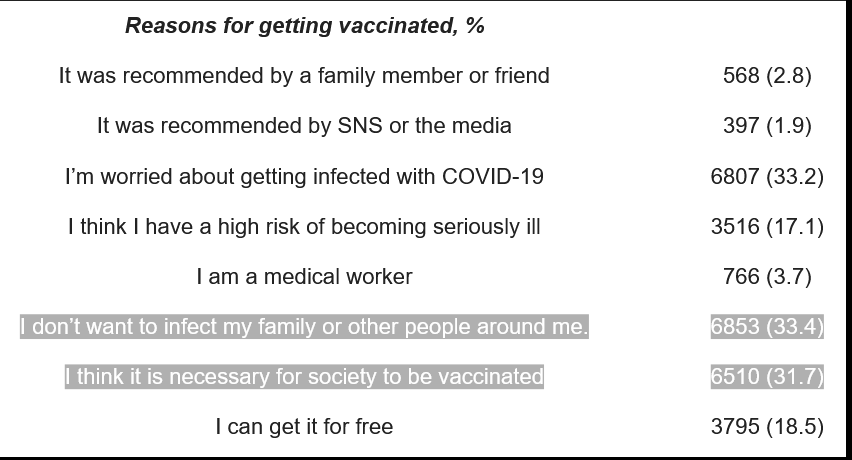

Those who were willing to join the world’s largest clinical trial responded that they didn’t want to get infected (33.2%), didn’t want to infect others (33.4%), or believed it was necessary for society (31.7%). Note that more people chose “I can get it for free” (18.5%) than “I think I have a high risk of becoming seriously ill” (17.1%). Interesting priorities.

Results of a multivariate logistic regression also found the vaccine skeptics were significantly more likely to distrust the government and the distrust the government’s Covid policy. And who can blame them?

Similar results were obtained by Nomura et al., who surveyed 30,053 Japanese over 20 in Feb 2021 about whether they intended to get the Covid vaccine: 55.1% said “yes”, 33.9% said “not sure”, and 11% said “no”. Their main findings were,

the perceived risks of COVID-19, perceived risk of a COVID-19 vaccine, perceived benefits of a COVID-19 vaccine, trust in scientists and public authorities, and the belief that healthcare workers should be vaccinated were significantly associated with vaccination intention.

Again, safety and effectiveness were the top reasons for being unsure or unwilling.

But the most interesting results are found in the supplementary material. 66.6% (an ironic number) of respondents willing to vaccinate thought it would ease their anxiety! I wonder how that’s worked out for them.

But the results of the below question are even more interesting.

81.4% of the vaccine willing agreed that you should get vaccinated if others do so, compared with only 6.7% of the unwilling. I imagine they feel the same about mask wearing: you should do it because everyone else does.

What about trust in the public authorities? Pretty much as you’d expect.

Overall, these results suggest the vaccine willing wanted to get jabbed because they suffered from media-induced anxiety about Covid and trusted the government’s assurances that the jabs would benefit not just themselves but others too. In contrast, the vaccine skeptics were worried about whether the jabs would affect them negatively and didn’t trust the government to guarantee safety. They also seemed more immune to media fear-mongering and peer-pressure.

Post-campaign surveys

Nomura et al. re-surveyed 19,195 of the original respondents a year later in Feb 2022.

Of the 19195 respondents to the second survey, 1980 (10.3%) responded ‘no’ and 6097 (31.8%) responded ‘not sure’ regarding their intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in the first survey. Of each, 928 (46.9%) and 4933 (80.9%) reported having received or intending to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in the second survey.

It’s unsurprising 80.9% of those initially on the fence got off on the jabbing side when you consider the intensity of all prominent individuals and organisations shouting “It’s safe & effective! Do it for those around you!” for months on end. But why did 46.9% of the initially unwilling give in? Nomura et al. identified six clusters.

Cluster 1 (n = 122, 13.2%) that still has had concerns about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine but has begun to recognize the benefits of vaccination in general; Cluster 2 (n = 125, 13.5%) where short-term concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine have been dispelled by someone close to them who received the COVID-19 vaccine; Cluster 3 (n = 187, 20.2%) with no clear overarching reason; Cluster 4 (n = 50, 5.4%) that considers the COVID-19 vaccine necessary for work and personal relationships; Cluster 5 (n = 273, 29.4%) that has begun to recognise the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine and its social significance with respect to controlling the spread of infection while concerns about short-term and future adverse reactions remain; and Cluster 6 (n = 170, 18.3%), for which concerns about short-term adverse reactions and the safety of COVID-19 vaccine have been dispelled to some extent.

Interestingly, only 5.4% got jabbed for reasons to do with work and personal relationships, and 29.4% had a change of heart while still harbouring concerns about safety. On the other hand, many of the initially skeptical came to the conclusion that the jabs were more effective and safer than they thought. That’s certainly what TV said, but I’m not sure that’s what the data shows.

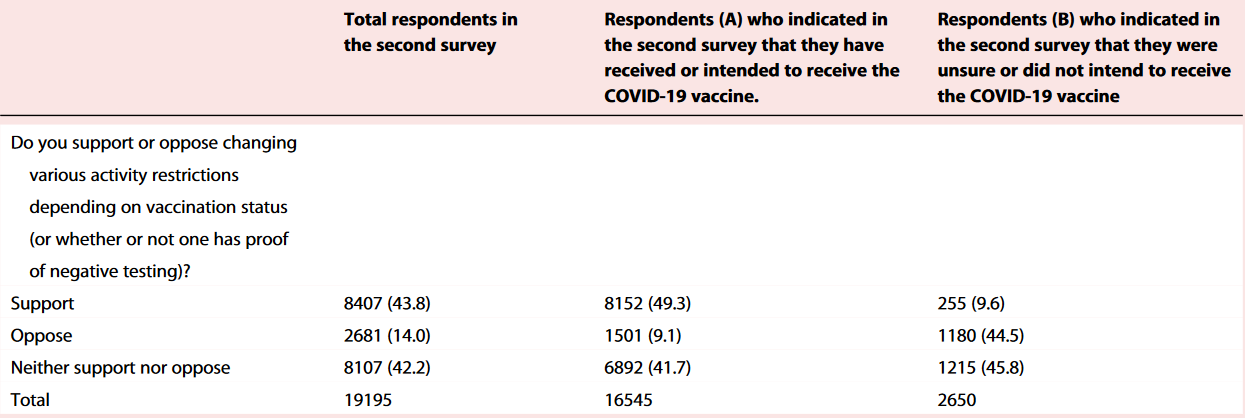

Nomura et al. also asked the survey respondents a new question regarding support for the government’s Covid vax/negative test pass [1]. Obviously, the willing were much more likely to support than oppose (49.3% vs 9.1%) and the skeptics were the opposite (9.36% vs 44.5%).

The skeptics were also asked whether vaccine/negative test requirements would persuade them to get the jab. Only 7.5% said “yes”.

The low percentage of “yes” responses is to be expected since these are people who managed to resist an intense propaganda campaign and accompanying peer-pressure. It’s fair to say they’re hard to manipulate.

Bear in mind this survey was done before the government’s statistical shenanigans inflating vax effectiveness came to light. And the negative test option allows restriction supporters to say the unvaxed aren’t actually being restricted.

So what about people who were initially willing but later changed their minds?

In a separate study with the same re-surveyed 19,195 respondents, Ghaznavi et al. re-found…

Of 11,118 (57.9%) respondents who previously expressed interest in vaccination, 10,684 (96.1%) and 434 (3.9%) were in the vaccine willing and hesitant groups

So only 3.9% had changed the minds from willing to unsure or unwilling. So what made them different from the willing jabbers?

Several covariates were found to significantly predict vaccine hesitancy, including marital status, influenza vaccine history, COVID-19 infection/testing history, engagement in COVID-19 preventive measures, perceived risks/benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine, and attitudes regarding vaccination policies and norms.

Basically, single people who don’t usually get flu jabs and had caught Covid already weren’t as interested in the Covid jabs as they were the year before.

Like those who were skeptical to start with, the newly skeptical were also much less likely than the willing to agree they should be jabbed just because everyone else is.

They were also 2.6 more likely to oppose vaccine discrimination/coercion.

They were also 3.87 times more likely to think the disadvantages of the jabs were large and 4.36 times more likely to think they were very large.

So the newly skeptical valued individual liberty and were concerned about vaccine safety.

I’ll mention one more study. Arashiro et al. surveyed 2500 people in November 2021 and compared the 86.6% who had or intended to be vaccinated with the rest who had no intention or preferred not to answer. They found that…

Persons who did not intend to be vaccinated were less likely to be afraid of getting infected (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.32, 95% CI 1.53–3.53), family members getting infected (aOR 2.50, 95% CI 1.68–3.71]), infecting others (aOR 2.58, 95% CI 1.73–3.84), and bed shortages caused by a surge in severe COVID-19 cases (aOR 1.89, 95% CI 1.25–2.87).

In other words, they were less likely to think Covid was that big a deal.

Arashiro et al. also surveyed the respondents on their social behaviours (meeting friends, dining out, travelling, etc.) and found “no association between vaccine intention and engaging in potentially high-risk behaviors.” I bring this up because a common excuse put out by Japanese vax advocates to explain low vaccine effectiveness estimates is that the jabs are effective, it’s just that vaccinated people engage in higher risk behaviour because they feel safer and more secure. I’d say that explanation was always more convenient than convincing.

So what can vax skeptics learn from this data to better dissuade people from taking shoddy shots?

Highlight that the known risks of the Covid vaccines greatly outweigh their exaggerated benefits.

Point out the untrustworthiness of the government and media. There are plenty of examples of broken promises at this point.

Emphasise that medical decisions should be made for oneself, not for others. “I don’t want to infect granny” is not a good reason to take a jab that won’t stop you infecting granny.

Tell people Covid really isn’t that big a deal, especially not for low-obesity East Asians. Even the Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases admits as much now.

If you can think of any others, add them in the comments. The government and media put a lot of effort into thinking of ways of persuading people to get the jabs…

…so the skeptical side needs to do the same if it wants to dissuade them.

[1] Compared with the pharma-fascism in Canada and Austria, Japanese government’s vax pass (called the vaccine/test package) wasn’t much of a threat to liberty. The government envisioned the package being used for access to full-capacity events and for buying alcohol in bars & restaurants during emergency/quasi-emergency periods.

But the spread of Omicron led to the government’s advisors advising against using the package. Nevertheless, Saitama Prefecture instituted a no-jab, no-drink policy during that last quasi-emergency period, as described previously.

Wonderful ,thoughtful article. Hope you are connected to others who are able to engage in this type of data analysis like Steve Kirsh and Dr Jessica Rose to name a couple ,of the many brilliant minds ,like yourself, out there .

Interesting info. I think in the US they realized there wasn't much buy-in anymore with only half of the vaxxed getting boosted. And almost no one bothered getting double boosted unless they were over 50.

https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total