The first two years of Covid in Japan: turning immunological victory into economic defeat

The Canadian Medical Association Journal recently published the following paper.

One of those peer countries was Japan, which gives us a chance to use the data in the main paper and supplementary material to see how Japan compared with the peer countries too. Japan had the fewest Covid deaths and excess deaths per million…

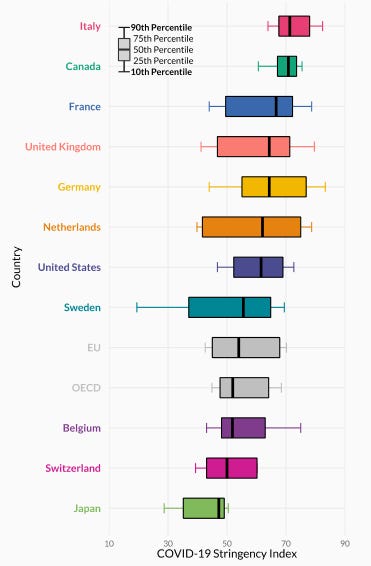

…and the least stringent response [1].

But as I’ve mentioned before, Japan’s Covid low mortality rate is mainly due to immunological factors and its low stringency is due to its constitution (for now).

Specifically, it’s thanks to its constitution that Japan had 0 days of stay-at-home or workplace closure requirements, although most people greatly reduced their mobility and most “non-essential” businesses closed as requested during the first state of emergency (SoE) in April/May 2020

So by not being able to hobble itself as much as its peer countries, Japan must have outperformed them economically, right?

Er, so zero growth. But unlike the others, I bet Japan didn’t have to prop up its economy with huge amounts of debt spending.

So why despite its immunological and constitutional advantages was Japan such an economic laggard?

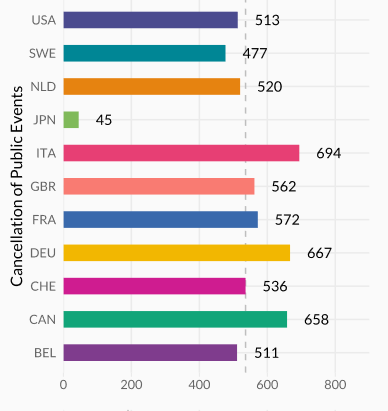

One clue is in the data for public event cancellations. Japan only cancelled public events nationwide for 45 days during the first SoE in April/May 2020 and restarted sports with spectators in mid 2020, far earlier than its peer countries.

But even though events in peer countries went back to normal in 2021, Japanese sports games still have capacity limits and fans still have to follow dumb rules like chanting only while socially distanced, masked, and facing forward. For the events sector, July 2020 and July 2022 aren’t greatly different.

Also, SoEs or quasi-emergency measures were introduced on and off in various prefectures during January-September 2021, but prefectural governors generally limited themselves to requesting that bars and restaurants (B&Rs) operate only between 11:00 and 20:00 and not offer alcohol. But thousands of establishments in Japan’s major cities stayed open later and offered booze without suffering any penalty.

Anyone who had to live through the strict lockdowns in other countries will probably read the previous paragraph and think “That was it!?” But the restrictions are only half the story. Japan’s peer-pressure and the stigma toward people who test positive for Covid lead to not only a high voluntary vaccination rate but also high levels of compliance with stay-at-home requests, which the Oxford Stringency Index can’t capture.

Additionally, even though the Covid restrictions tend to be local, the Covid propaganda is national: news about cases in Tokyo leads to people in Tottori staying home more. The below graph from Nikkei Business shows the number of internet searches for B&R information in regions where B&R restrictions were shorter and longer compared with the 2015-2019 baseline. In 2021 and early 2022, searches were higher in the regions with shorter restrictions but still well below the the pre-pandemic baseline.

The effects of governors’ pointless demands for “self-restraint” are even clearer when comparing retail-and-recreation mobility in 2021 between Japan and high-growth Sweden and America.

The one area where the Oxford Stringency Index can somewhat reflect the Japanese mentality of prioritising Covid over everything else is border controls. The below graph actually understates Japan’s border closure as it only counts the days Japan’s border was officially closed to people from all countries (Jan 2021 to Feb 2022) as opposed to most countries (April-December 2020).

But these numbers can’t capture unhinged policies like classifying everyone on a plane as close contacts when one passenger tests positive or requiring tourists to be accompanied by North Korean style chaperones to ensure they’re constantly masked.

But is there anything Japan deserves a pat on the back for? One thing Japan is comparatively praiseworthy for is closing schools for a relatively short period (March-May 2020), thus better protecting children’s education. Note that Sweden never fully closed schools, with primary schools open throughout.

But like with events, Japan may have reopened schools earlier, but its continued Covid measures in schools like masking at almost all times have inflicted misery upon Japanese school children for over two years now despite all evidence they aren’t needed.

To sum up, the Japanese were protected from Covid by their immunological defences, but rather than admit this, Japan’s media and politicians have regularly repeated economically harmful lies about the need for Japanese people to stay home and foreigners to stay out. Of course, if they admit the truth, they’d essentially be admitting there’s no need for mRNA vaccines or expanded emergency powers either. And we can’t have that now, can we, Fumio?

[1] In case you were wondering why Sweden has a higher average stringency score than Belgium and Switzerland, it’s because the the guys in charge of the Government Response Tracker retroactively increased Sweden’s score by treating the Prime Minister’s recommendations as de facto requirements. True story. See the thread below.